This is a version of the poster and/or ad art that MGM used to try to sell Garbo Talks to moviegoers in 1984. I actually like the simplicity or whimsy of this poster quite a bit and even though its style is consistent with the film’s animated title sequence, it’s a failure as a movie marketing tool. It looks more like a children’s picture book cover than a poster for a seriocomic tale of a dying woman’s last wish. (Michael says it reminds him of A Charlie Brown Christmas.) Almost nothing significant of the plot is revealed, right? Of course, studio execs are loathe to let on that any movie features someone suffering a terminal illness. Too much of a downer. Then, of course, there’s the little matter of the illustration and how the female looks rather generic. She certainly does not look like the mother of the male figure. Here again, the studio opted out of promoting the star power of Anne Bancroft, a proven Oscar winner in her early 50s at the time, but playing a character likely a decade older. Again, a dodge designed to “fool” younger audiences, lest they be turned off by a movie about a mature woman. When the movie’s early box office returns proved anemic, the studio regrouped and issued a new ad featuring an image, lifted from the film, of Anne Bancroft in a funny pose, surrounded by quotes from reviewers lauding her performance, alas, not to be found on the Internet. The male figure, btw, scarcely resembles Silver, an actor I first noticed on the old Rhoda sitcom, but I digress. “Sometimes,” the poster’s tag reads, “you can catch a star.” Sometimes, as well, people whose job is is to sell movies are timid or have no idea how sell a movie that does not present instant appeal to 14 year old boys. (IMAGE: IMDB)

Have you heard? Director and sometime writer Sidney Lumet, a five time Oscar nominee who passed away in 2011, is the subject of a new documentary, By Sidney Lumet (directed by Nancy Buirski). I hope to see it because I am a huge Lumet fan. He had one of the most distinguished careers of any filmmaker of his era even though his only Oscar was of the honorary distinction. I missed the fairly recent documentary about Brian De Palma, so maybe I’ll be more diligent about this new offering.

So, here is what has happened. A couple of years ago, David Itzkoff wrote a book entitled The Making of Network and the Fateful Vision of the Angriest Man in Movies–that “Angriest Man” might appear to be a reference to the stark raving anchor man played to Oscar’s hilt by the late Peter Finch, or even Lumet himself, but it’s actually directed toward screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky, also an Oscar winner, Network‘s true guiding force. I don’t necessarily love the 1976 feature that inspired Itzkoff’s tome–but then, I’m not sure that “love” is what anybody had in mind when the greenlight was given to make a movie that takes (took) aim at the corrupt world of television and its crippling effect on society as a whole. That noted, the things I like about the film, I like a whole heck of a lot; after all, Academy nominations for 5 performances, among a host of nods, with three winners is pretty impressive. Anyway, Michael gave me a copy for my birthday, and between that and my Network DVD and all its extras, I was in Lumet heaven for about a week or so.

I got so caught up in my Network mania, that I pulled out my copy of Lumet’s own book, Making Movies. Of all the many, many books I have on the business of making movies and “behind the scenes” accounts of many classic films, Lumet’s book ranks incredibly high on my list. He takes the reader through the step by step process of how he makes movies, including a run-down of an average day on one of his sets, but Lumet also devotes each chapter to a particular facet of moviemaking: developing a script, scouting locations, casting actors, rehearsing, shooting, editing, etc. Into this account, he weaves recollections of specific situations over the course of his illustrious career, devoting a lot of ink to 12 Angry Men, Long Day’s Journey into Night, The Pawnbroker, Network, Prince of the City, and The Book of Daniel. I don’t think he completely skips over Murder on the Orient Express, Dog Day Afternoon, or The Verdict–I know he doesn’t–but he doesn’t write about them as vigorously, it does not seem, as the others. Interesting that he invests as much as he does in Prince of the City and, especially, The Book of Daniel since they are not necessarily among his more esteemed entries. The latter, based on E.L. Doctorow’s fictionalized account of the aftermath of the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg executions (starring Timothy Hutton) was pretty much a dud–on the heels of the highly successful The Verdict, no less. Lumet even details some of the obstacles he faced while trying to film his ill-fated big screen adaptation of the hit Broadway show The Wiz on location in New York City.

Sidney Lumet is one of my faves among faves. In his storied career, he earned 5 Oscar nominations: 4 as Best Director (12 Angry Men, Dog Day Afternoon, Network, and The Verdict) and another as co-adapter, with Jay Presson Allen, of the screenplay for 1981’s Prince of the City. Alas, he never won a competitive Oscar in spite of being one of the most prestigious, and most consistent, directors of the 1970s and 1980s. The Academy finally saw fit to bestow an honorary award to him in 2005. Better than nothing, but consider the following: the quartet of movies for which he earned directing nods were also Best Picture nominees; moreover, his films garnered a total of 18 performance nominations with a total of four wins: Ingrid Bergman (Best Supporting Actress, Murder on the Orient Express, 1975), Faye Dunaway (Best Actress, Network, 1976), Peter Finch (Best Actor, Network, 1976), and Beatrice Straight (Best Supporting Actress, Network, 1976). Network, by the way, is one of only 15 films to boast acting nominations in all four performance categories (with William Holden, also Best Actor, and Ned Beatty, Best Supporting Actor, rounding out the bill). Furthermore, only Network and A Streetcar Named Desire can boast acting wins in 3 of the 4 acting categories, with no film claiming 4 for 4 so far. Per AMC Filmsite, Lumet is tied for 6th place among directors with the most acting nominations and also 6th place among directors with the most acting winners. (IMAGE: IMDb)

One movie that Lumet scarcely mentions in his book is 1984’s Garbo Talks. There are probably at least two understandable reasons why this film in particular is not among Lumet’s priorities. First, Garbo Talks is not a typical Lumet film, meaning his speciality, the massive undertaking known as The Wiz or glamorous Murder on the Orient Express notwithstanding, is gritty drama: the dirt and grime of the big city, betrayal, corruption, the seamy underside of what should be our bedrock institutions. In other words, Lumet’s approach is hard hitting in a way that does not signal comedy, and Garbo Talks is quite a peculiar comedy since one character’s impending demise is announced fairly early. In spite of that, the movie proceeds on an oddball, mostly light-hearted, course. To clarify, Lumet often brings out the humour in bizarre situations, as evidenced in both Dog Day Afternoon and Network, but the emphasis is never on jokes, punch lines. The humour in those movies stems from discomfort, human foibles, and the absurdities of life’s hard-knocks. Garbo‘s laughs are more obvious though, again, juxtaposed with the scenario of a dying woman. The second reason that Lumet might not want to go on and on about Garbo Talks is the simple fact, owing no doubt to the first reason, is that it sank at the box office. Most moviegoers probably couldn’t get their heads around the idea of Sidney Lumet making a comedy, about a dying woman, no less. It didn’t help, of course, that despite some encouraging reviews, especially for star Anne Bancroft, MGM didn’t really know how to market the thing.

Moving on, here is what interests me about Garbo Talks. In his book, Lumet makes a point of differentiating what a movie is about as opposed to its plot. For example, the plot of Garbo Talks, scripted by Larry Grusin, concerns a devoted, if exasperated, thirtysomethingish son, Gilbert Rolfe (Ron Silver) trying to fulfill his dying mother’s lifelong wish of meeting Greta Garbo by tracking down the reclusive cinema icon in [then] modern day New York City, encountering a cast of colorful characters along the way. That’s the plot. But what is the function of the plot, what purpose does it serve? What, again, is this movie about? I’ll tell you what I think it’s about. And I hate ending sentences with prepositions, by the way. I think what Garbo Talks is really about is a man and his relationship with windows.

Let me back-up just a bit. I saw Garbo Talks TWICE in theatres back in its minuscule run back in the fall of 1984, and one of the things that made a lasting impression on me was how Lumet framed two characters, two actors, against windows with almost magical views of New York City. Even though Lumet famously shot many movies on location, as opposed to Hollywood sound stages, I feel pretty certain that many of this film’s interior scenes were filmed on sets of some kind, okay, sure, in NYC, and not Hollywood. The point is the views from the handsome town home of Gilbert’s dad, played by Steven Hill, and the strikingly spacious yet “homey” loft of a chirpy young actress (Catherine Hicks) are likely fakes, backdrops that are too good to be true. Stunning, yes, but not the real deal. No matter. Of course, earlier in the movie, before Gilbert’s mother discovers how seriously ill she is, Gilbert’s boss reassigns the young man, an accountant, from the office in which he has comfortably settled into less accommodating quarters. Gilbert is horrified, and he explains that the new office doesn’t have a window like his old office. Gilbert says that. I heard him, but I didn’t pay much attention to it the first time, not even the second time; however, I began to see the bigger picture, so to speak, eventually.

So, this is a movie that I once owned on VHS, and now I own it on DVD, per MGM’s print-on-demand boutique. Anyway, I have seen it several, several, times since 1984, and at some point I began noticing how many times actors are framed against windows, not just the two I noticed during those early viewings, and I made the connection between Gilbert’s dreary windowless office, seen more than once but only specifically commented on twice or so, and all those shots emphasizing oh so many windows. Lumet’s uncharacteristically flat framing, practically proscenium style (like a play) accentuates window placement in almost every set, most often splayed across back walls. Visually, it’s barely more than a filmed play, with only a small handful of scenes requiring more than two actors–almost always a giveaway that the material was originally conceived for the stage though that is not necessarily the case.

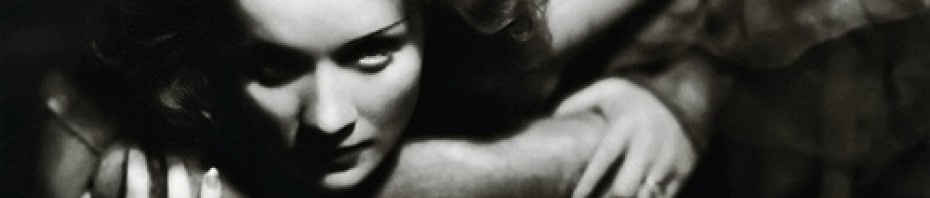

This publicity still features Ron Silver (l) and Anne Bancroft (r), neither of them quite in character (but not NOT in character), with Garbo herself depicted in the background. Estelle Rolfe is one of Bancroft’s most vivid, yet tricky, characterizations. She’s first seen misty-eyed watching an old Garbo movie in bed late at night, and the audience is primed to think of her as a harmless old lady. The next time we see her she’s in jail, more or less for an act of not-so-civil disobedience, followed by another sequence in which she lashes out at a construction crew yelling lewd remarks at females passing their site. Rolfe isn’t having any of it. Harmless old lady, indeed. Bancroft earned a well-deserved Golden Globe nomination for Best Actress in a Musical or Comedy, but the movie was not a significant enough achievement, in spite of many favorable notices, to warrant Academy recognition though as I recall, no less than Today Show movie critic Gene Shalt harrumped that that year’s batch of Best Actress hopefuls, including stars of three movies depicting women trying to save their farms (Sally Field, Jessica Lange, and Sissy Spacek) would have benefitted from the comedic spark provided by Bancroft, Kathleen Turner (Romancing the Stone), Mia Farrow (Broadway Danny Rose), and, possibly even Shelley Long (Irreconcilable Differences); meanwhile, one of my good friends, while no less enthusiastic about Bancroft’s performances than I was, figured a Best Actress nomination might have been a stretch since Bancroft’s screen time is noticeably limited compared to Silver’s in spite of the incredible monologue. My friend opined that Bancroft’s monologue wasn’t enough to elevate what is essentially a supporting performance to leading status. I’m not sure I agree, but it’s an interesting take. (IMAGE: MGM via MovPins)

I thought I understood. Those windows remind Gilbert of what he’s missing–at least per his office. No windows. Then, I made a point of paying closer attention to Gilbert’s apartment. Any windows there? Hmmmm….Lumet has one more trick up his sleeve.

Gilbert and his dutiful, if whiny, wife (played by Carrie Fisher) keep quite a tidy little apartment, not at all lavish. Slightly cramped as, in an effect seen multiple times throughout the film, the living area doubles as the sleeping area. For most of the movie, consistent with the aforementioned static staginess, Gilbert seems in need of a window both at the office and at home. Maybe occasionally Lumet hints at the possibility of an apartment window just outside the camera lens, and, okay, the pass-through between the kitchen and the dining area is window-like, but the director withholds the moment of truth for as long as possible before revealing that, yes, indeed, Gilbert’s apartment does have a window…but wait…Lumet, you rascal, you. What unfolds in Gilbert’s life, what shifts, just before Lumet literally turns the camera to show the view from Gilbert’s window?

If you have the access and inclination, I think there are two ways to watch Garbo Talks. First, watch it for the sweet, strangely satisfying tale that it is, the story of a nice Jewish boy trying against almost impossible odds to take care of and please his highly opinionated whirlwind of a mother, a woman who lives to speak out against social injustice, big or small, and to take respite, to revel in, the singular beauty of old-time Hollywood’s most elusive movie star. Notice, how, for instance, Gilbert’s wife and his stepmom seem so strikingly in-sync as though Gilbert had followed his dad’s lead when finding a [new] mate, someone as different from Estelle as possible in the service of self-preservation. Luxuriate in Anne Bancroft’s especially skilled performance, most notably a rapturously single-take monologue in which Estelle recalls her first ever Garbo experience and the many times since when she’s found comfort, refuge, and excitement in the films of her cinematic idol. Notice how Silver, as Gilbert, looks at his mother with such a sweet mix of love, admiration, and exasperation. Relish Silver’s expert timing, his control, as Gilbert navigates a final, pointed confrontation with his prig of a boss (played by ever reliable Richard B. Shull). Take delight in well-etched supporting performances by the likes of Hicks, Hill, Howard Da Silva as a worn-out paparazzo, Dorothy Loudon as a true show-biz eccentric, and Hermione Gingold as a doddering actress who has seen better days–but not by much.

After watching Garbo Talks for the plot and the performances, take it in again–this time focusing on the windows: when and where they appear, how many in a given locale, their various sizes, and their relationship to the actors in a given shot. Maybe turn the sound down, if not off entirely. It’s like a different movie, one seemingly oblivious to Bancroft’s Estelle and her plight, and oblivious even to Garbo. It’s all about windows. The mystery then remains as to why Lumet uses windows the way he does in the film. What point does he want to make? Gilbert makes compromises, as we all do, even if that means denying something that holds value for him: his tiny office window. His mother, of course, is not so mundane as all that. She won’t be swayed until she has given her all to righting a wrong, again, no matter how big or small. Even when she loses, she’ll stick around long enough to spit out the last word. That’s who she is. “We are who we are,” she says. Does she make others around her uncomfortable? Yes, very much so, and that is why Gilbert lets go of petty office politics as often as he does, as easily as he does. Thus, Gilbert does not fight for what he believes. Instead, he gets pigeon-holed into a windowless box. Estelle Rolfe says repeatedly that she has always accepted the given fact, meaning that in her mind she picks her battles carefully and only commences to blitz when the evidence favors her position. Yet, as a wise man once told me, facts are the enemy of truth. Yes, Estelle Rolfe says what she says, but what she does is quite different. When it suits her, she skews the facts to suit her purpose.

This is the lesson that Gilbert must learn as he embarks upon his quest to find Garbo. He looks through other people’s windows and forgets the fact that if he’s feeling boxed-in, he can rewrite the given fact…because, after all, he has a window, a different window, away from his office, that offers a different set of facts if only he takes the time to consider all possibilities.

Well played, Mr. Lumet, well played.

Thanks for your consideration…

AMC Filmsite: http://www.filmsite.org/bestdirs1.html

Garbo Talks at the Internet Movie Database: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0087313/

Sidney Lumet at the Internet Movie Database: http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0001486/

Silver and Bancroft: http://www.movpins.com/dHQwMDg3MzEz/garbo-talks-(1984)/still-1059554560