Per the IMDb, a clerical error regarding “copyright” status in the credits rendered Charade as part of the public domain immediately upon its 1963 release. Luckily, Criterion has a super-edition that features lively commentary by director Stanley Donen and scriptor Peter Stone. Admittedly, part of the fun is listening to these well-seasoned pros bicker–good naturedly–as they hash their sometimes hazy memories of a movie they filmed decades earlier.

So, there we were watching 1980’s Hopscotch, the non-sequel that reunited 1978’s House Calls stars Walter Matthau and Glenda Jackson in the same way that 1979’s Lost and Found reunited George Segal and Jackson in a non-A Touch of Class sequel. Interesting, isn’t it, that in such a brief period Jackson reteamed with high-profile co-stars in new projects.

Hopscotch, directed by legendary Ronald Neame, whose credits include everything from The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie to The Poseidon Adventure, is a heck of a lot of fun as Matthau’s intelligence operative goes rogue rather than settle into forced retirement. Ever-reliable Matthau has great fun as the CIA equivalent of a wascally wabbit. He even notched a Golden Globe nod. The script, based on a novel by Brian Garfield, was nominated for both a Writers Guild award as well as the Poe prize. Well done. Jackson could have phoned in her performance, but she didn’t. Again, she and Matthau are in fine form. [Please note: Matthau was 60ish at the time, and Jackson was in her mid-40s, but make no doubt that the two humans they’re portraying definitely hold a sexual attraction for the other, and that’s nice to see.] Plus the thing was filmed all over the place: Savannah, London, Munich, and Salzburg. For some reason I thought Paris put in a cameo, as well, though that’s not confirmed on the IMDb (nor in the DVD featurette).

Seeing Matthau in this light-hearted caper brought back fond memories of Matthau in 1963’s Charade, top-lined by Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn. Charade, set in Paris and directed by Stanley Donen (Singin’ in the Rain), has often been pegged the best Hitchcock movie that Hitchcock never made, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

Hepburn plays a widow whose murdered husband lived a double-life. Grant portrays a shadowy figure who often arrives either at the nick-of-time when Hepburn is in peril, OR he appears suspiciously at the most inopportune time. Matthau pops up for a few scenes as a bumbling bureaucrat at the U.S. Embassy. He makes the most of his screen-time, still a few years shy of winning a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for The Fortune Cookie.

FYI: The rest of the Charade cast includes two more future Oscar winners, James Coburn and George Kennedy, in addition to Ned Glass. They’re like a goon squad that may or may not have conspired to kill Audrey’s Charlie.

Charade ignited a mild controversy or two during its original run. First, consider that the movie opened in early December of ’63, barely two weeks after the assassination of President Kennedy (yes, in Dallas, TX). As detailed in his commentary, even director Donen questioned the appropriateness of Hepburn and Grant using the word “assassinated” (and its variants) in one scene. The director alleviated that concern by quickly arranging to have the “offensive” dialogue dubbed (or redubbed), substituting “eliminated” instead. Not a seamless transition but serviceable given the gravity and immediacy of the matter. Another cause for alarm came about due to the comparatively high body count. Now, this may seem spectacularly difficult to grasp in the post-Pulp Fiction, post-Saving Private Ryan, post-Saw era, but we’re talking only five. Five dead bodies, total. Five dead bodies with hardly a speck of blood between them, but the censors argued that the deaths were treated casually, or, worse, humorously. Per Donen, he had to slightly rework a scene in order to appease the standards and practices watchdogs.

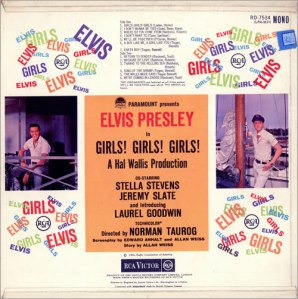

Fresh from his Charade triumph, director Stanley Donen signed on for another round of cinematic cloak and dagger with Arabesque (1966). The frothy thriller, filmed in and around swingin’ London, plays much campier than Charade, making even Hitchcock’s delightfully convoluted North by Northwest seem positively restrained. Arabesque‘s plot is purely nonsensical, but the striking visuals and mid 1960s “mod” quotient help make the blasted thing imminently watchable. Per the IMDb, Peck was not the director’s first choice for the male lead. That honor reportedly went to Charade‘s Cary Grant, but the actor was ready for retirement and especially not interested in playing a romantic hero opposite a much younger female co-star. He’d already expressed a similar concern during the production of Charade. Critics may carp that Peck is miscast as an American scholar at Oxford, but I get a kick out of the way he seems to be channeling Grant, adding another layer of fun. In many ways, this is Loren’s movie. Oh, she doesn’t give a performance in any way comparable to, say, her Oscar winning Two Women. Mainly, she’s used as a clothes horse, averaging what appears to be one Christian Dior costume change per scene. That’s right, Dior. Well, if Audrey Hepburn can insist on Givenchy, Loren is equally entitled to wardrobe by Dior. (In this case, more likely Marc Bohan designing for House of Dior and netting a BAFTA nod as well.) Of course, Loren, so sheerly beautiful, dazzles in one close-up after another though she lacks Hepburn’s vulnerability. The Italian superstar plays an Arab mobster’s mistress who may know more about a secret code than she cares to share with Peck. Arabesque is by no means a classic, but while it wasn’t a huge hit on the order as Charade, it wasn’t a flop either [3]. Existing on a level somewhere between James Bond and The Pink Panther, both of which were in vogue at the time, it’s all good fun with music by Henry Mancini, and a title sequence designed by Maurice Binder. Tell me this poster doesn’t read as “Bond-esque.” No extras on the DVD–if you can find it.

So, as our Hopscotch night turned into a Hopscotch/Charade double feature, I thought about what a swell movie Charade is, and I’ve thought so ever since I first saw it. Instantly captivated, I was. That was, gosh, decades ago. I’m pretty sure the occasion was a Saturday night late show, probably channel 8. I think I was babysitting. Anyway, I was biting my nails in suspense the whole time, from one twist to the next and all the way through the climactic showdown in and around the famed Palais Royale (a combination of the actual Palais Royale, a less historic theatre better suited for shooting interiors, and an intricately designed set).

The next day, after the double-feature, I had a thought. I remembered that Alternate Oscars author Danny Peary bravely, if not brazenly, elected to NOT award “Best Picture” any 1963 release. Peary’s argument is that while there were still a number of good films that year, none of them were up to the standards of, say, Lawrence of Arabia, which had won the previous year, or even West Side Story, the 1961 victor. Of course, this flies in the face of what the Academy awards represent: the achievements of any given year for better or worse. The record is what it is. I actually wrote about this very thing in May of 2012.

On the other hand, Peary makes a point, however misguided. 1963’s Best Picture line-up probably leaves something to be desired. Peary argues that Best Picture winner Tom Jones looks smug and dated these days, and, in retrospect, it may have very well received a boost at ballot time from the British invasion that began sweeping the country in February of 1964. Seems plausible. The other nominees represent extremes. On one hand, there’s Cleopatra, lavish, yes, but bloated and–let’s face it, Liz–badly acted. Talk about irony, the film sold enough tickets to be one of the year’s top earners even though it didn’t sell nearly enough tickets to recoup its enormous, record breaking, production costs. On the other hand, Elia Kazan’s America America, a three hour black and white movie inspired by his emigrant father, seems to have had no lasting impact, not that it achieved anything close to mainstream status at the time. What about How the West Was Won? A huge hit, no doubt, but the three-strip Cinerama extravaganza is practically unwatchable in anything but its widescreen glory. That noted, it now takes its place among the classics in the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry.

Historically, the odds were against the fifth nominee Lilies of the Field (which earned Sidney Poitier a historic Best Actor trophy [2]) as Ralph Nelson was shut-out by his peers in the directors branch. Oh, and that omission actually tips the scale even more in Peary’s favor as Kazan and Tom Jones‘s Tony Richardson were the only directors among the five Best Picture nominees recognized by the Academy, the other three slots accorded to Federico Fellini (8½), Otto Preminger (The Cardinal), and Martin Ritt (Hud). Okay, Peary almost makes sense. How can three of the year’s five Best picture nominees not have corresponding Best Director nods, and how can the films of three nominated directors not be included among the five Best Picture slots? Again, maybe Peary has a point.

In Charade, Audrey Hepburn plays vulnerability and wide-eyed panic so well that it’s hard for audiences to resist; however, Gary Grant may very well have the more difficult assignment, essaying a character whose motives, much like his name, seem to change from one scene to the next. Is he really protecting Miss Hepburn from danger, or is he danger personified? It’s a tricky balancing act, and Grant performs with aplomb, but he covered similar territory in at least two Hitchcock films: Suspicion (as Joan Fontaine’s scheming husband) and To Catch a Thief (the prime suspect in a series of jet-set burglaries). Luckily, his charm and sophistication remain intact in his last great film role.

Even though Peary refuses to honor any 1963 film with his phony award, he includes a list of his personal favorites along with some well-regarded also-rans, including The Nutty Professor, The L-Shaped Room, The Birds, Jason and the Argonauts, the aforementioned Hud, and a few others. And no Charade. What, no Charade? It occurred to me to double-check Peary’s 1963 entry, and there it was, or, rather, there it wasn’t. I started this blog to write about movies that somehow failed to make the cut with Oscar voters, but now I find myself wanting to defend a film that didn’t even make an imaginary list of sub-par contenders. How can that be? Did Peary just forget that Charade came out in 1963? Would his chapter for that year have turned out differently if I had been there to put a bug in his ear? After all, the IMDb was still in its infancy when Peary wrote his book. Maybe he just didn’t have as many resources as I did/do.

Still, Peary can write whatever he wants in his own book. I can’t fault him for that though I am a little stunned that someone who basically writes off a whole year’s worth of output can still find praise for the likes of The Nutty Professor, Jason and the Argonauts, The Birds, etc., without also seeing some value in such a popular and generally well liked enterprise as Charade. What’s not to like? [To clarify, I’m a fan of many of the movies Peary likes, especially Jason and the Argonauts–that’s not my gripe.]

That noted, I’ll allow that the oft-repeated favorable comparisons to Hitchcock might be a tad hasty. Of course, I’m not real big on the word “Hitchcockian” though I have been known to use it from time to time, so, okay, I’m guilty. My concern about the term at all is that it’s lazy or sloppy and not even always appropriate. In the case of Charade, the usage is almost justified considering Grant’s presence; after all, the quick footed, charismatic leading man enjoyed great success in such Hitchcock films as North by Northwest and To Catch a Thief. Even Donen and Peter Stone acknowledge the superficial similarities to the latter, what with Grant and the gorgeous travelogue footage of the French Riviera as well as the larky tone and the budding romance between the two impossibly glamorous leads, yet Ms. Hepburn definitely does not fit the bill of the typical Hitchcock icy blonde goddess, such as To Catch a Thief‘s Grace Kelly, who smolders just beneath the surface. In contrast, Hepburn is brunette, approachable, and vulnerable.

Golden Globe nominees Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn cavort all over Paris in Stanley Donen’s comedy-thriller Charade. Hepburn previously worked with director Stanley Donen on 1957’s Funny Face, partially filmed in Paris, as well as 1967’s Two for the Road with Albert Finney, also shot on location in France. Many critics, including Danny Peary, herald the pair’s final collaboration as Hepburn’s finest performance though she was Oscar nominated, instead, for the same year’s Wait Until Dark. Prior to Charade, Grant worked with Donen on Indiscreet with Ingrid Bergman.

Also, Charade‘s set-up is more straightforward than many–but by no means all–Hitchcock films in that Stone’s script plays more as a whodunit whereas Hitchcock tends to favor cat and mouse scenarios. Think about it. Consider, oh, just about any Hitchcock film: Rear Window, Shadow of a Doubt, Rope, Strangers on a Train, and Frenzy. In these films and others, there’s little or no question about the murderer’s identity. The dilemma is how long before the good guy catches up with the bad guy. In Charade, the first murder takes place within seconds. Nothing is known about the either the victim or the assailant though at least three possible suspects are introduced in short order.

Additionally, one of Hitchcock’s signatures is that the audience usually knows more at any given moment than the characters do. Look no further than Vertigo, in which tension builds as the audience waits for the moment when leading man James Stewart snaps to the deadly duplicity that has already been revealed in another character’s flashback; however, in Charade, the action unfolds from the perspective of Hepburn’s widow, so almost without exception the viewer only knows as much as she does. Still, Charade includes what Hitchcock once labelled the “MacGuffin,” that is, the elusive “thing” that everybody wants and which serves as the catalyst for much of the plot. In Charade, Donen turns this one’s “reveal” into a doozy of a surprise, one that caught me off-guard for at least the first 2-3 times I saw it, years apart I might add, but that’s what makes the movie so much fun.

Some highlights include Grant and Kennedy sparring atop the American Express building, or rather, a studio re-creation of said building’s rooftop, bringing to mind the rooftop climax of To Catch a Thief. Even so, while the location has clearly been faked, Donen insists that what the audience sees is Grant, upwards of 60 at the time, doing much of his own footwork. Keep in mind that before he became a Hollywood star, Grant worked as an acrobat. Oh, and soundstage trickery is evident in a pretty well-executed scene in which the two stars enjoy a dinner cruise down the Seine. The sequence begins with an actual location establishing-shot before cutting to Grant and Hepburn framed against a filmed plate of Paris at nightime, but Donen does his best to sell the illusion through a clever sound mix that involves a slight echo when the vehicle passes under a bridge. There’s also a nifty Paris Metro sequence which leads to the Palais-Royale showdown in which the action cuts back and forth among three vantage points in the darkened, cavernous theatre.

I love Charade so much, and think that’s it’s so complete as is, that I could never imagine watching Jonathan Demme’s 2002 remake, The Truth about Charlie with Mark Wahlberg and Thandie Newton. Since the Demme version tanked, I guess no one else was interested in seeing a classic defiled either. And that’s the real truth about Charlie. I wonder what Danny Peary has to say about that.

Thanks for your consideration….

IMAGE from Pintrest: https://i.pinimg.com/originals/d2/cb/d0/d2cbd05b78f6416358818abbec2a462d.jpg

^ In many ways, Maurice Binder’s Charade title sequence is reminiscent of Saul Bass who designed the opening credits for such high profile Hitchcock films as Vertigo, North by Northwest, and Psycho–all to the strains of Bernard Herrmann’s thrilling scores, but Binder was no mere copycat. Binder, who died in 1991, was one of the most influential designers in the biz, responsible for conceptualizing the look of the James Bond credits as well as 1987’s Oscar winning The Last Emperor (one of my all-time faves), in addition to Donen’s Arabesque and Two for the Road among many many others. Binder featured at Art of the Title: http://www.artofthetitle.com/designer/maurice-binder/

[1] According to an article by Jeff Stafford on the Turner Classic Movies website, Charade actually outpaced Hitchcock’s The Birds at the box office. The figures listed in Cobbett Steinberg’s book, Reel Facts: The Movie Book of Records, published in 1978 by Vintage Books (a division of Random House) support Stafford’s assertion though, keep in mind, that as a late 1963 release, Charade most of its money in 1964. Click here to access Stafford’s piece: http://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/3838/Charade/articles.html

On the other hand, the lists of 1963’s top earners on the IMDb and Wikipedia are much different. I can’t explain the difference–re-releases, adjustments for inflation–since until fairly recently industry figures were reported in rentals, that is, the fees paid to studios from exhibitors based on percentages of ticket sales. Almost nothing was reported in grosses–even as late as Steinberg’s book–though a safe bet, as it was once explained to me, is that a gross could be figured my multiplying the rental by 2.5 Read more at Box Office Mojo: http://www.boxofficemojo.com/about/boxoffice.htm

[2] Interestingly, Peary strips Poitier of his win and favors Jerry Lewis (The Nutty Professor) instead, listing only official nominee Rex Harrison (Cleopatra) as a finalist; likewise, Peary elevates official nominee Leslie Caron in The L-Shaped Room (one of my mother’s faves) over actual Best Actress winer Patricia Neal (Hud): Peary, Danny. Alternate Oscars. New York: Delta (a division of Dell), 1993. 168-171, 190-191.

[3] Per Steinberg’s book, Charade was 1964’s 4th biggest earner while Arabesque tied for 14th in 1966.

Charade at the IMDb: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0056923/?ref_=nv_sr_1

Hopscotch at the IMDb: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0080889/?ref_=nv_sr_1

Arabesque at the IMDb: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0060121/?ref_=nv_sr_1